This experimental prototype was part of my 8-year research journey that led to Workshop Workshop.

MMM

Meaning Making Machine

The Vision

The MMM represents was the final project for my MA/MSc in Global Innovation Design, embodying my explorations into recommendation models for object customisation. The original vision was to create an environment encouraging participants to engage with various stimuli, uncovering their preferences so the data could feed into a model creating bespoke meaningful objects.

Due to time constraints and budget limitations, I scaled down from a full environment to designing a singular touchpoint: a decision that greatly influenced the project's trajectory.

The Question Behind it

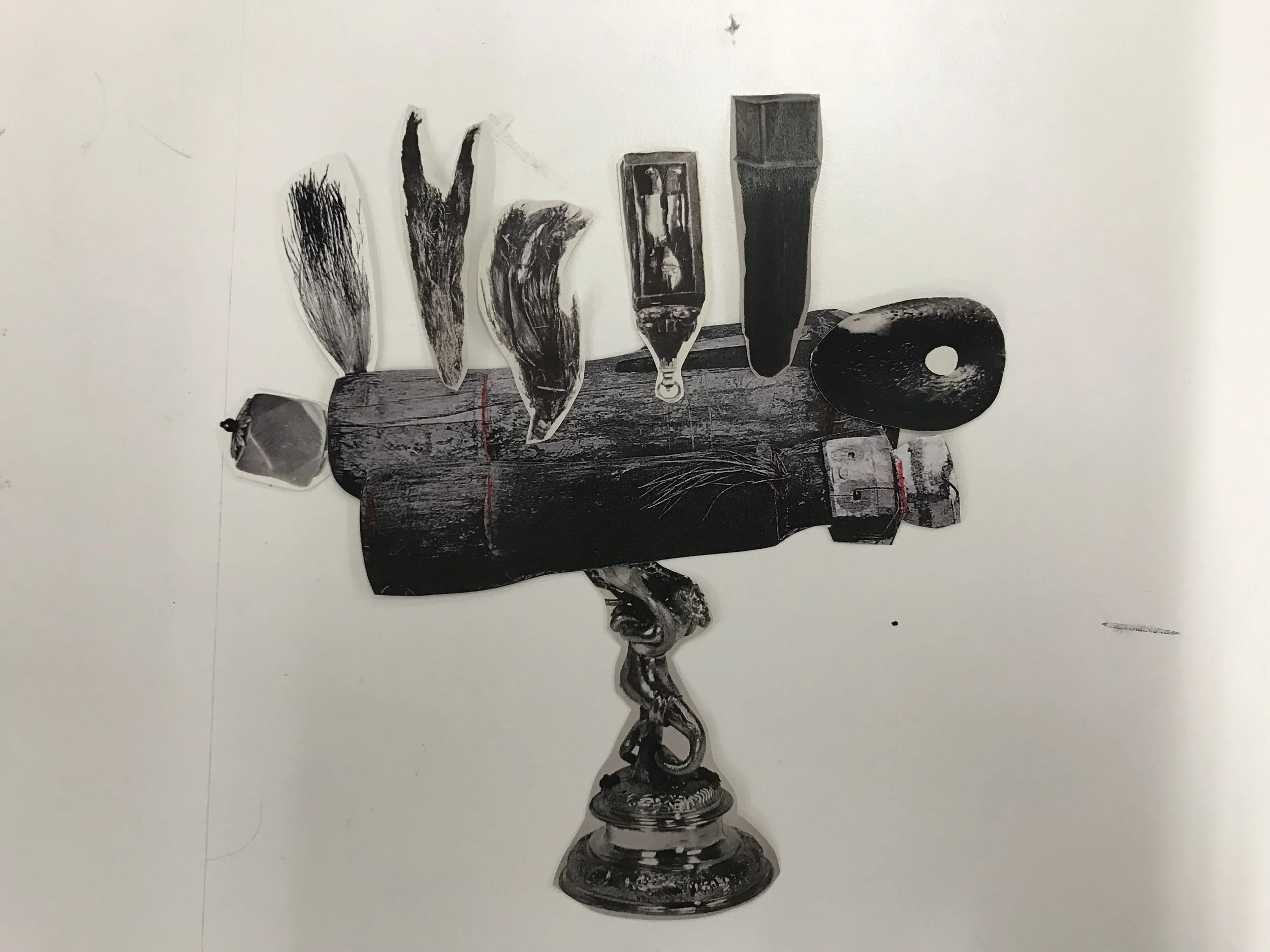

The concept stemmed from inquiring about what made certain objects feel meaningful. If I combine two objects with different meanings, does the resulting object become meaningful in a different way? Antiquity is full of meaningful objects, amulets remain popular worldwide even though the beliefs that originally enabled them have changed.

I started visiting museums and interviewing people about their relationships with objects they considered meaningful. Less sophisticated examples like Pandora bracelets were everywhere, but I was envisioning something deeper and more personal.

Technical Implementation

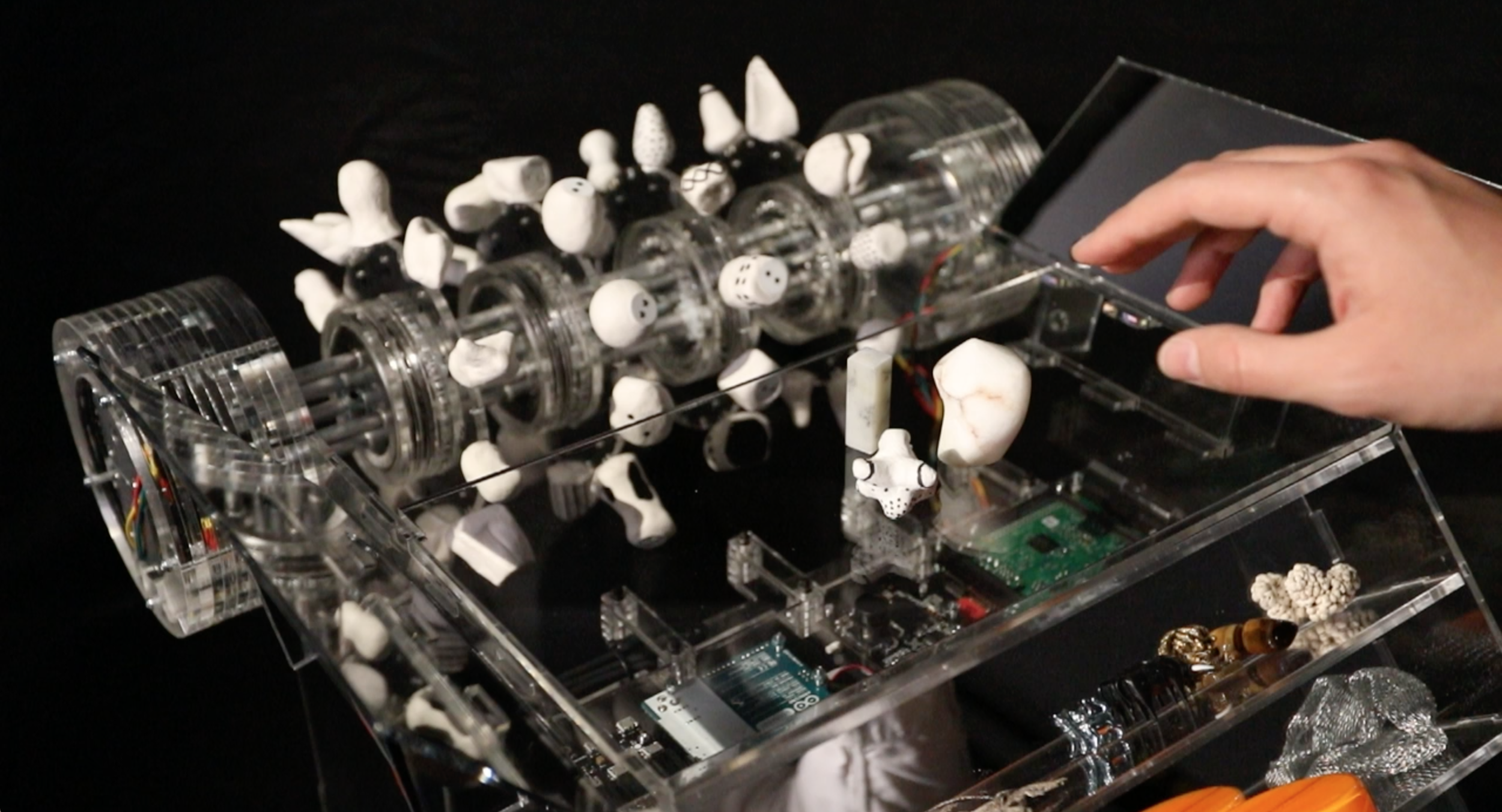

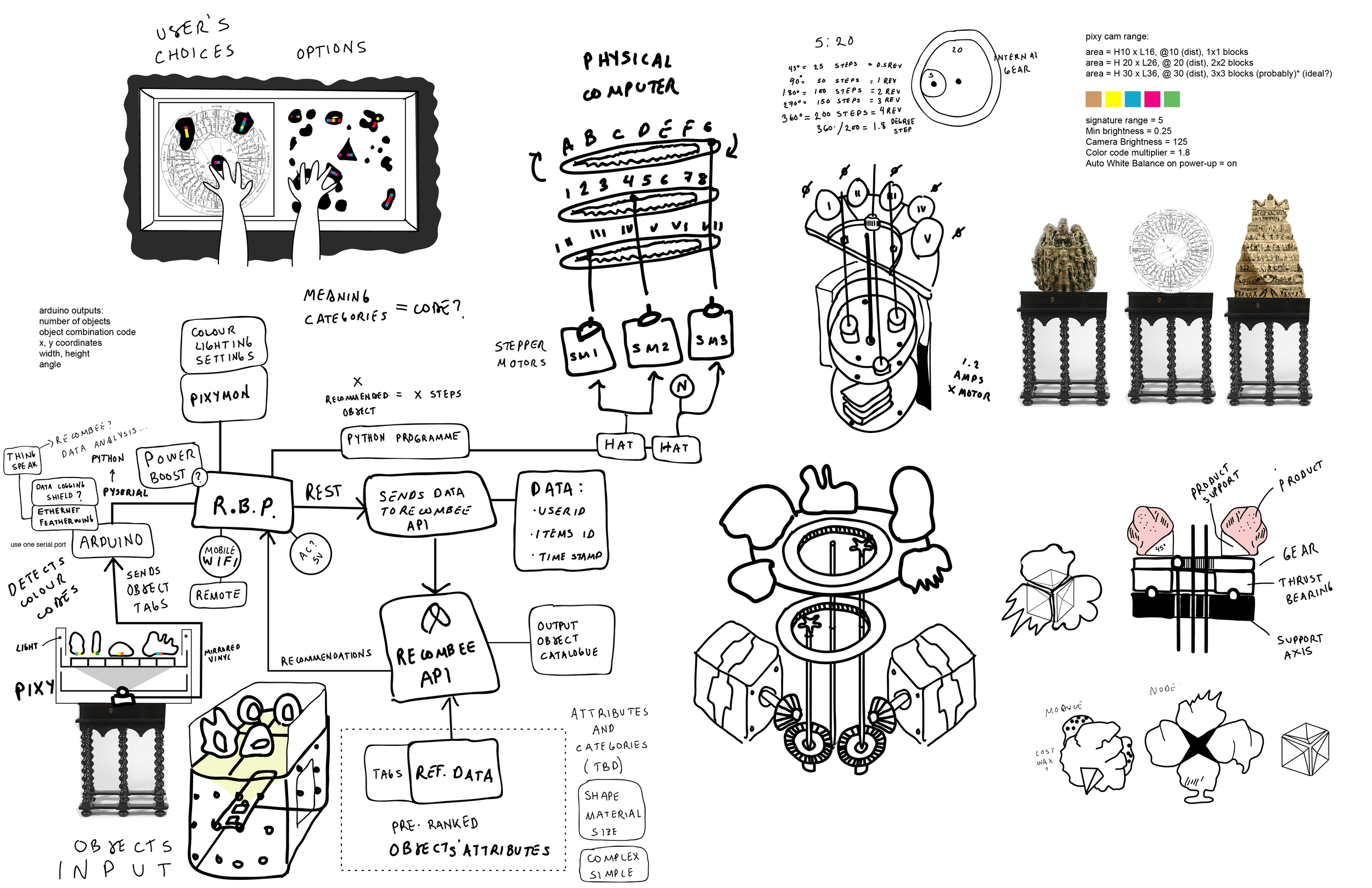

The machine quantified user interactions through a sophisticated system. Participants would choose objects following prompts I provided, then place them on the machine's top tray. Each object had a tag, and sensors beneath the tray identified these tags, capturing user choices.

Creating the combination mechanism required treating it like an architectural project, where each decision influenced others. I chose transparent materials to demystify the process, allowing participants to see the inner workings and enhance their understanding.

The Modular Amulet System

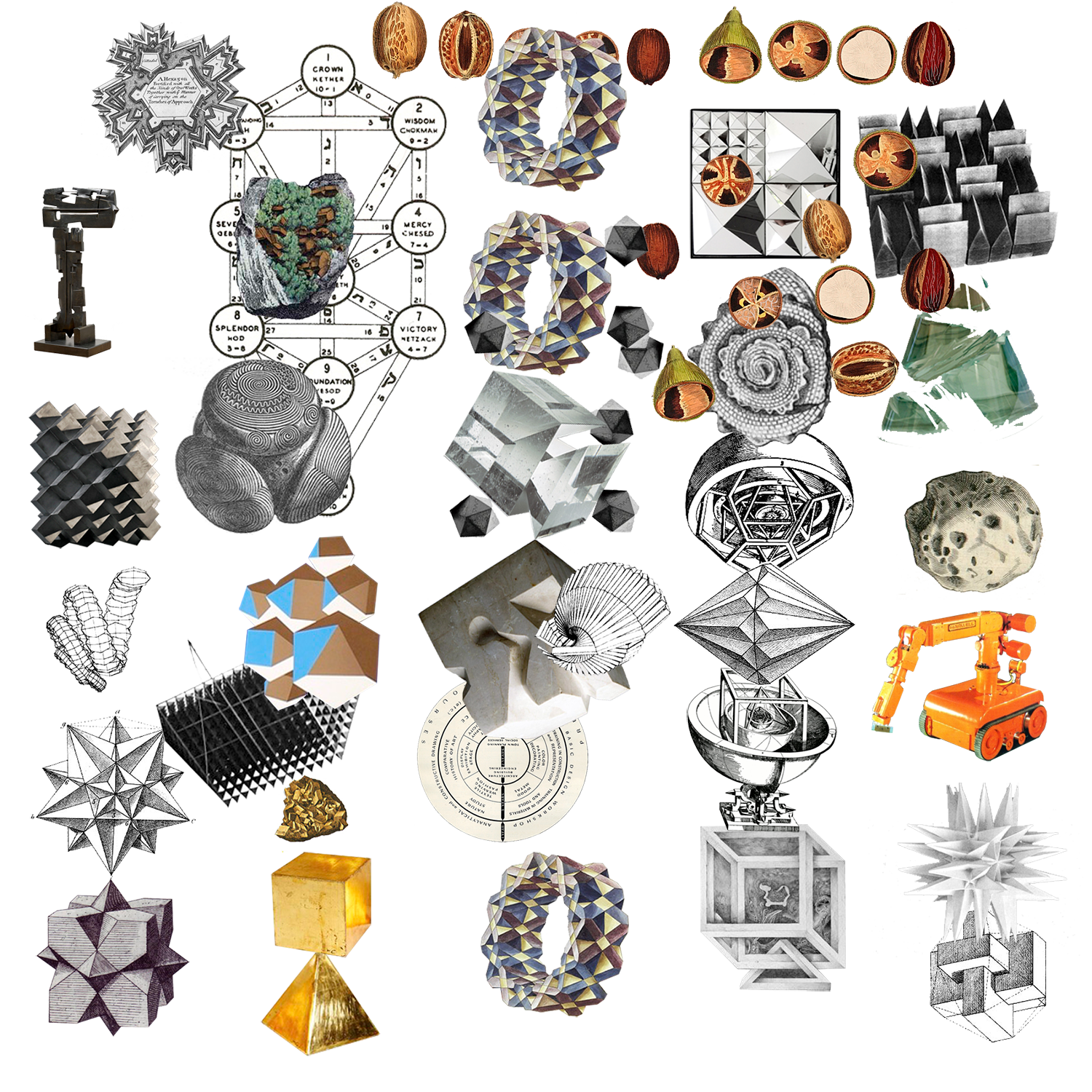

The MMM became a physical machine designed around creating modular amulets. I used a recommendation engine typically used in e-commerce, building a database of varied objects contributed by artists including Cristina Carbajo, Melisa Leñero, Andriana Nassou, Jessica Gregory, Sadi Yetkili, and Kelly Fung.

To gather initial data, I asked volunteers to classify objects into categories both subjective ("ugly - beautiful") and objective ("small - big"). This approach was crucial for beginning to understand how people ascribe value and attributes to objects.

The Results

Creating the final objects posed significant challenges. My initial idea of using elements from various religious deities was set aside due to cultural sensitivity concerns. Instead, I opted for abstract objects crafted from clay using magnets for attachment. While respectful, this choice made it harder for participants to connect with the final object, leading to somewhat underwhelming results.

What I Learned

The MMM was more than just a machine, it was an ecosystem uniting various components: object repository, interaction interface, electronics, and combination mechanism. But the technical sophistication couldn't overcome the fundamental issue:

meaningful objects require genuine personal connection, not algorithmic assembly.

Reflecting on the project, I recognise areas for improvement, particularly around understanding users' connections with meaningful objects and ensuring reliable data collection. A key oversight was the lack of feedback loops for continuous model improvement.

Developing MMM in 2015, before concepts like Surveillance Capitalism were widely discussed, I initially viewed behavioural data extraction positively. In hindsight, I recognise the need for more ethical approaches to such practices.

MMM taught me that meaning can't be manufactured through clever algorithms. it emerges from process, relationship, and personal connection, not from the final object itself.

AI and Meaning-Making: A 2017 Experiment's Relevance Today

MMM was essentially an early experiment in using artificial intelligence to create meaningful experiences - specifically, a recommendation system powered by machine learning algorithms attempting to understand and generate personal significance through physical objects.

This approach now feels remarkably prescient given today's discussions about AI's capabilities and limitations. The system could identify patterns in user preferences and execute sophisticated combinations, but it struggled with something more fundamental: genuine meaning-making requires human processes that resist algorithmic replication.

The project revealed a crucial distinction between pattern recognition and understanding. While the AI could detect correlations in user behavior and preferences, it couldn't replicate the cultural context, personal history, and emotional resonance that actually make objects meaningful to people. The most significant moments happened not when the machine delivered its algorithmic recommendations, but during conversations people had while using it - the human reflection and connection that the technology couldn't capture or reproduce.

This limitation feels especially relevant as we navigate today's AI landscape. Current systems excel at pattern matching and generating outputs based on training data, but they still struggle with the deeper human experiences that MMM attempted to address: genuine understanding, cultural sensitivity, and authentic meaning-making.

The lesson from MMM wasn't that AI is useless for human experiences, but that it works best as a tool for facilitating human connection rather than replacing it - an insight that continues to guide my current work